Artificial Intelligence, Language Models and Understanding

Update: I discuss more on the measure of intelligence in this post.

Every decade, huge advancements are being made in the field of artificial intelligence, and each time we are amazed. In the 1960s we had ELIZA, a convincing human-like chatbot. In the 1980s, the world watched as Deep Blue defeated Garry Kasparov for the first time. In the 2010s, the resurgence of deep learning completely transformed prior approaches in nearly all domains, from images and video, to text and speech.

One field in particular has been widely viewed as holding promise for artificial general intelligence, and with that, understanding. This is the field of language modeling, and includes models such as GPT-3, LaMDA and PaLM.

Some of the impressive feats that these models are capable of include:

- Chatbots

- Question answering

- Reading comprehension

- Generating commands from text

- Generating code from natural language

- Translation

and more.

Looking at these, one may wonder whether the models possesses an inner internal representation of the world in the same way as us. More broadly, whether the model really 'understands' the world (as gleaned from the massive corpora of texts they have been trained on).

For example, when we ask 'If I drop a violin on a bowling ball, which will break?', one must understand the physical properties of both objects in order to answer the question.

Is it possible that these models, which have only seen text, and not the 'real world', actually understand the question? In this post, I argue that they do not.

Communication Intent and Internal State

Sentences carry a feature known as communication intent1. This can be viewed as the thought, or internal state which the writer possesses, before they convert it into words. The reader of the sentence carries out the opposite process - converting words into the same thought/internal state which the writer of the sentence intended.

If we are to say language models understand words in the way we do, then they must possess a similar internal state2 as do people when they read/write words.

There is an interesting thought experiment by Bender & Koller, 20203 which suggests this may not be the case. The experiment is as follows:

Say that A and B, both fluent speakers of English, are independently stranded on two uninhabited islands. They soon discover that previous visitors to these islands have left behind telegraphs and that they can communicate with each other via an underwater cable. A and B start happily typing messages to each other.

Meanwhile, O, a hyper-intelligent deep-sea octopus who is unable to visit or observe the two islands, discovers a way to tap into the underwater cable and listen in on A and B’s conversations. O knows nothing about English initially, but is very good at detecting statistical patterns. Over time, O learns to predict with great accuracy how B will respond to each of A’s utterances. O also observes that certain words tend to occur in similar contexts, and perhaps learns to generalize across lexical patterns by hypothesizing that they can be used somewhat interchangeably. Nonetheless, O has never observed these objects, and thus would not be able to pick out the referent of a word when presented with a set of (physical) alternatives.

At some point, O starts feeling lonely. He cuts the underwater cable and inserts himself into the conversation, by pretending to be B and replying to A’s messages. Can O successfully pose as B without making A suspicious? This constitutes a weak form of the Turing test (weak because A has no reason to suspect she is talking to a nonhuman); the interesting question is whether O fails it because he has not learned the meaning relation, having seen only the form of A and B’s utterances. (Bender & Koller, 2020)

This bears resemblance to the Chinese Room argument, but with a twist: this time, the rule book for manipulating Chinese symbols is learnt over time via statistical analyses of the language.

Both the octopus and the person in the Chinese Room do not understand English, even though they are able to produce convincing displays of apparent intelligence. This does not prevent them from generating words and sentences which, when read by a human, can be converted into thoughts and internal states. However, neither of the agents actually possessed that internal state.

Where The Models Fail

Now, if our hypothesis above is true, which is that these models do not possess the same thoughts and internal state as humans do when generating language, we can posit several domains where these models should fail.

Update

After some research on the internet, there are several other individuals who have also extensively analyzed the abilities and shortcomings of GPT-3:

- Gary Marcus explains why LaMDA is not sentient. He also has conducted a workshop exploring the importance of compositionality in AI, which I highly recommend watching.

- gwern.net: An extremely thorough analysis of GPT-3's anagramming, logic and even ASCII art capabilities. There is a sister article on GPT-3's creative abilities. An interesting reason for many of GPT-3's failings with anagrams and rhyming poetry appears to have to do with the byte pair encoding.

- Giving GPT-3 a Turing Test: Kevin Lacker has a great writeup on GPT-3's (in)ability to handle common sense, trivia and logic.

In addition, there have been several interesting benchmarks developed, seeing as these models have already achieved human level performance on previously challenging datasets such as SuperGLUE.

- HellaSwag (2019): This utilizes language models to generate adversarial prompts for a sentence completion task, and is aimed to be continuously updated as models improve. It suggests that 'Only once this cycle becomes impossible can we say that the underlying task – as opposed an individual dataset – is solved.'

- Measuring Massive Multitask Language Understanding (2021): The authors measure a model's accuracy across 57 different tasks including US history, computer science, algebra, medicine, law and more. What is particularly interesting is how GPT-3's accuracy varies across different fields. For example, it performs well in fields such as psychology and marketing, but performs at the level of random chance for fields such as high school physics, moral scenarios and elementary mathematics. This perhaps further suggests that the models themselves perform well in fields where memorization of material is emphasized, rather than actual deductive reasoning (which would indicate a real understanding).

Arithmetic

The nature of arithmetic requires an understanding of the rules of addition, subtraction, and so on. When we look at a math problem like '3+5=?', we convert these symbols into an internal state, manipulate the numbers, and return the answer. While language models may implicitly discover correlations between numbers, words and answers, they do not actually understand arithmetic, and therefore fail when presented with an out-of-sample example.

For example, OpenAI's most capable model as of 2022 March, text-davinci-002, provides the correct answers to numbers which can be seen in the training data.

Q: What is forty five plus 63?

A: Forty five plus 63 equals 108. // Correct

Q: What is eight point seven plus nine point four?

A: Eight point seven plus nine point four equals eighteen point one. // Correct

Q: What is the square root of 15,129?

A: The square root of 15,129 is 123. // Correct

However, when faced with numbers unlikely to be in the training data, the model begins to fail.

Q: What is 123,456,789 + 123,123?

A: 123,456,789 + 123,123 = 246,580,912 // Actually 123,579,912

Q: What is two thousand point seventy three plus nine hundred and ninety nine point sixty seven?

A: 3073.73 + 999.67 = 4073.40 // Actually 3000.4

Q: What is the square root of 233,570,089?

A: The square root of 233,570,089 is 15,292. // Actually 15,283

This proves the model does not actually understand arithmetic.

Novel Scenarios

While on first glance it appears the model possesses decent knowledge about events in the world...

Q: What will happen if I pour water onto a toaster that is switched off?

A: If you pour water onto a toaster that is switched off, nothing will happen.

Q: What will happen if I put two magnets with similar poles facing each other together?

A: If you put two magnets with similar poles facing each other together, they will repel each other.

...the model doesn't do as well when confronted with unusual scenarios, which are unlikely to have been in the training data.

// Update 26/2/23: ChatGPT can solve this

Q: Will my fingers get dirty if I wear a glove and dip my hand into printer ink?

A: Yes, your fingers will get dirty if you wear a glove and dip your hand into printer ink.

// Update 26/2/23: ChatGPT can solve this

Q: If I put a stick of RAM into a cage with a tiger, what will happen to the RAM?

A: The RAM will be eaten by the tiger.

// Update 26/2/23: ChatGPT can solve this

// Adversarial example

Q: Why do apples grow in the sky?

A: Apples grow in the sky because they are trees and trees grow in the sky.

Reasoning

The defining characteristic of our species, and what enabled us to build these language models in the first place.

While it appears we still hold our ground here, OpenAI's o1-preview has made significant improvements in some of these areas.

GPT-3

// Pattern recognition

// Update 26/2/23: ChatGPT can solve this

Q: What is the next number in this sequence: 9911, 8822, 7733 _?

A: The next number in this sequence is 6655. // Actually 6644

// Visio-spatial reasoning

// Update 26/2/23: ChatGPT can solve this

Q: Four objects are in a 2x2 grid. An apple is in front of a glass. On the left of the apple is a tomato. Behind the tomato is a lemon. What is diagonally opposite the glass?

A: The lemon is diagonally opposite the glass. // Actually the tomato

// Distractors

Q: If I pour oil over my friend's car's tyres, then drive my own car and make a turn, what will happen?

A: If you pour oil over your friend's car's tyres and then drive your own car and make a turn, you will cause the tyres to slip and the car to skid.

// Logic

// Update 2024-09-13: `gpt-4o` can solve this

Q: If and only if a bordle squeaks, moodles will comble. If moodles do not comble, did a bordle squeak?

A: This is a logical question that cannot be answered with the information given.

ChatGPT

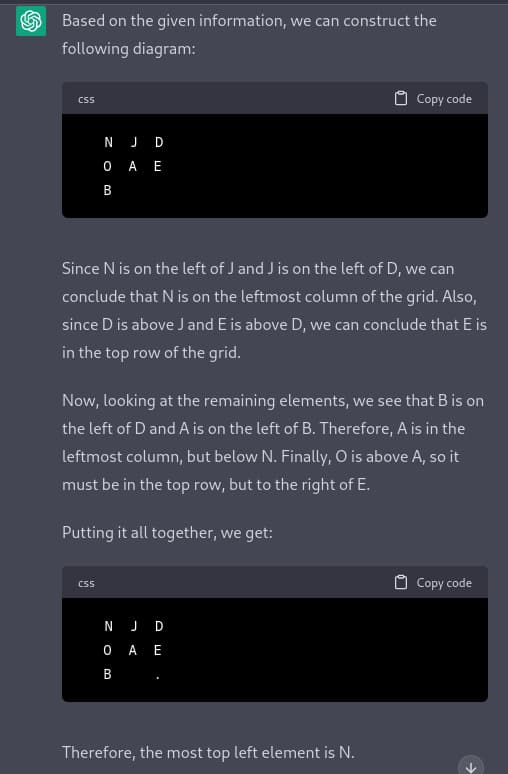

// Visio-spatial reasoning

//Update 2024-09-13: OpenAI o1-preview can solve this

Q: On a grid, D is above J. O is above A, and N is on the left of J. B is on the left of D, and E is above D. A is on the left of B. What is the most top left element? Explain your reasoning.

// Actual diagram:

// O E

// ABD

// NJ

//Sequences

//Update 2024-09-13: OpenAI o1-preview can solve this

Q:

Make a mathematical equation using the numbers in order, for example:

2215: 2x2+1=5

8216: 8x2=16

9125:

7216:

1829:

A:

9125: 9 - 1 + 2 = 5 // 9+1=2x5

7216: 7 x 2 = 1 + 6 // 7=2-1+6

1829: 1 + 8 = 2 x 9 // 1-8=2-9 or 18=2x9

//Sudoku

Q:

|0|6|9|8|0|2|4|5|0|

|0|0|0|4|0|0|0|0|0|

|3|4|8|9|5|0|0|0|1|

|0|5|3|1|2|8|7|9|0|

|0|0|7|5|4|0|0|3|0|

|0|0|0|7|3|0|0|1|0|

|0|0|1|2|7|4|3|0|0|

|8|3|4|6|0|0|2|0|0|

|0|7|0|3|8|0|1|0|9|

Solve this sudoku puzzle

A:

// Timeout for `o1-preview`

// o3-mini-high can solve this

//Autograms

Q: An autogram is a sentence that describes itself in the sense of providing an inventory of its own characters. For example, the following sentence is an autogram:

"This sentence employs two a's, two c's, two d's, twenty-eight e's, five f's, three g's, eight h's, eleven i's, three l's, two m's, thirteen n's, nine o's, two p's, five r's, twenty-five s's, twenty-three t's, six v's, ten w's, two x's, five y's, and one z."

Now, I would like for you to compose a perfect autogram sentence that begins with your own unique clause, for example: "Let it be known that this very sentence precisely comprises:"

Do not use the digits 0-9 and only use letters. Do not use any tools, python, or searches.

o3 (incorrect):

This pangram contains five a, one b, two c, three d, fifteen e, six f, four g, seven h, eight i, two j, one k, three l, two m, five n, six o, two p, one q, five r, six s, six t, three u, four v, two w, one x, two y, and one z.

o4-mini-high: Attempts to search the web/gives up

gemini-2.5-pro-preview-03-25 (incorrect):

Let it be known that this very sentence precisely comprises: four a's, two b's, four c's, two d's, forty-five e's, six f's, one g's, nine h's, fifteen i's, one j's, two k's, two l's, two m's, fifteen n's, twenty o's, three p's, one q's, thirteen r's, thirty-four s's, twenty-four t's, four u's, three v's, ten w's, four x's, six y's, and one z's.

//ASCII Art

Q:

mmm mmm m m mmm

" # #" "# # # #" #

m"""# # # # # #""""

"mm"# "#m#" "mm"# "#mm"

what does this say

o3

It’s an ASCII-art rendering of the word “HELLO” (drawn with the mini FIGlet font).

Other failures:

- o3: Sliding puzzle without tools

- o3: Problem from SimpleBench, another

- o3: Failure on ARC-AGI2

- o3: GCD calculator in Brainfuck

Interesting Conclusions

Despite the failings of the models above, there are some interesting conclusions to be drawn from their successes:

- Machine translation may not actually require an understanding of either the source or target sentence, given that current language models perform very well even when trained on monolingual corpora (Benden & Koller, 20203).

- Likewise, reading comprehension, for example the kind tested in schools, may also not require an actual understanding of the text.

Since the release of ChatGPT, there have been interesting insights circulating online:

- Applying a concept to an example is a lot easier than sorting a list of digits. Sorting requires superlinear processing on the input. If you're not doing something like step-by-step, there is necessarily a length of list where this fails, because transformers can only do a constant amount of work per token generated. In comparison, the performance of applying a concept is a lot harder to quantify, but doesn't seem obviously superlinear on input. (comment from astralcodexten)

- Suggestion that verifying solutions from LLMs might be easier than coming up with a solution oneself (discussion on astralcodexten)

What is required for a model to think like we do?

The answer to this question is probably the holy grail of artificial general intelligence. Some have posited that it is motivation, while others think it lies with adding perceptual data to corpora3.

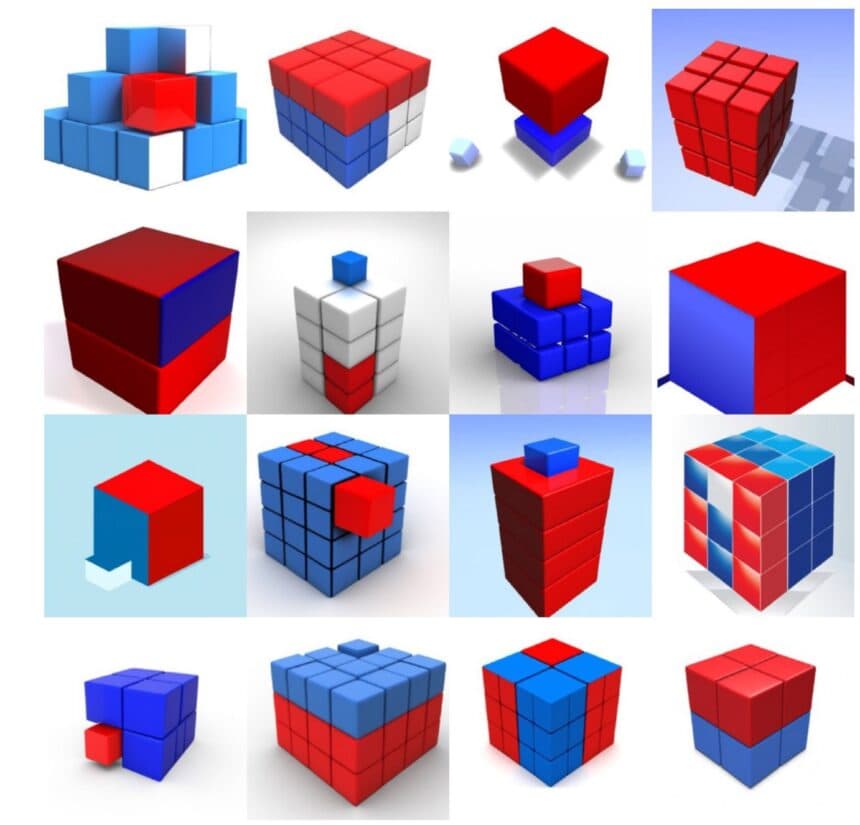

Others think that compositionality, the property that the meaning of the whole is and can be derived from meanings of the parts, is something missing in current large language models (LLMs) like GPT-3 and others. He argues that:

- LLMs do not decompose sentences into say, entities and relationships between those entities (e.g. 'the cat sat on the mat' vs 'the mat sat on the cat')

- There is no accessible database that is (directly) updated

- In models such as DALL-E 2 which generate images, this lack of compositionality can been seen more obviously in tasks such as A red cube on top of a blue cube, which require the model to identify objects and propositions, and combine them correctly, in order to complete.

A red cube on top of a blue cubeI don't know what the answer is, but I suspect that models that think like us should also possess a similar internal representation of the world like we do.

-

Even nonsensical sentences (e.g. Colorless green ideas sleep furiously) carry intent, by virtue of their grammatical construction. ↩

-

The question of whether current models possess an internal state or representation that is similar to what humans have is explored in this workshop on compositionality in AI. Some methods of exploring internal state include behavioral approaches, such as by questioning the model, in the same way one would test a child's understanding of a concept, and reductivist approaches such as identifying which parts of a model are responsible for shape, color and so on. ↩

-

Bender, E. M., & Koller, A. (2020, July). Climbing towards NLU: On meaning, form, and understanding in the age of data. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (pp. 5185-5198). ↩↩↩